News Americas, NEW YORK, NY, Mon. Feb. 9, 2026: On Super Bowl night, something happened that had very little to do with football and everything to do with who we think belongs to this nation.

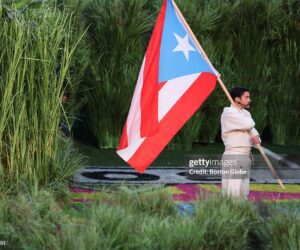

When Bad Bunny took the halftime stage and performed in Spanish, a familiar reaction rippled across the country. Some viewers were angry. Others were dismissive. Many questioned whether a Spanish-speaking artist from the Caribbean could “represent America.” The frustration was not subtle. It centered on language. On discomfort. On a belief that English, in one narrow form, is the only acceptable voice on America’s biggest stage.

That reaction made me think about home.

My daughter is Dominican. Her maternal family is Dominican, and her great-grandmother has never spoken a word of English to me. I do not speak Spanish; I was born in Jamaica. Yet for over a decade, every time I have seen her great-grandmother, she has greeted me warmly in Spanish. I never understood the words, and I never cared, because it never mattered. Not once did it make me feel unwelcome. Not once did it make me feel excluded. We smiled. We embraced. We understood one another without translation.

Language did not divide us. It connected us.

And yet, in this country, language often becomes a line of separation.

Across America, especially for those of us from the Caribbean, language carries history, rhythm, and identity. We arrive with accents, speech patterns, and expressions shaped by our islands and our ancestors. We bring Jamaican patois, Trinidadian cadence, Bajan lilt, Dominican Spanish, Haitian Creole. We bring voices that sound different from what many Americans are used to hearing.

Too often, the response is blunt and dismissive: Speak English. This is America.

What’s rarely acknowledged is that many are speaking English. Jamaican patois, for example, is rooted in English. It is English shaped by survival, resistance, and culture. It is not broken language. It is living language. When it is mocked or rejected, it is not because it lacks structure. It is because it makes some people uncomfortable.

That discomfort says more about the listener than the speaker.

I moved from Jamaica straight into an American high school. I learned early how the way I spoke shaped how people perceived me. Over time, my accent softened. Some people now say they don’t hear one at all. Others say it’s faint but still there. That lingering uncertainty, where are you from? How do you belong? It never really disappears.

Language does that. It becomes shorthand for assumptions.

That’s why the reaction to Bad Bunny matters. Puerto Rico is part of America. Spanish has been spoken on this land long before the NFL existed. Yet here we were, watching people debate whether they would mute their televisions, change channels, or boycott an event altogether because the performance did not sound like the America they were used to hearing.

What many missed is that asking Bad Bunny to perform in English would have stripped the performance of its authenticity. Spanish is his language. It is how his music breathes. Asking him to change that is not inclusion, it is erasure.

I do not listen to Bad Bunny’s music. But my daughter does. Her family does. And that matters too. Representation is not about pleasing everyone. It is about acknowledging who is already here.

The irony is hard to ignore. Many of the same people upset about a Spanish-language performance would gladly pull out a translation app if they traveled overseas. Closed captions exist. Translation tools exist. Curiosity exists when we choose to use it. Yet within our own borders, we sometimes refuse the same openness we expect from others abroad.

This is how progress stalls. Not through hostility alone, but through selective empathy.

Language is how people are seen. How they are heard. How they are understood. When we dismiss someone’s language, we are not just rejecting words, we are rejecting identity.

Sixteen years ago, had I closed my heart because I didn’t understand Spanish. I would have missed a welcome that required no translation at all. That moment taught me something simple but enduring: understanding begins with listening, not control.

If the Super Bowl taught us anything beyond football, it is that America is still negotiating its many voices. We can cling to one sound and call it unity, or we can listen fully, openly, and recognize that the chorus has always been bigger than we imagined.

The question is not whether language belongs on America’s biggest stage.

The question is whether we are willing to grow enough to hear it.

Support NewsAmericas

Related News

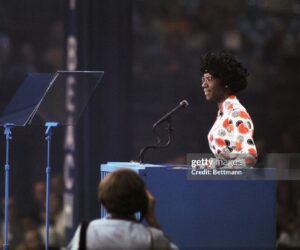

Caribbean American Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm’s Legacy Lives On In Brooklyn’s Litt...

The Cuban Revolution Holds Out Against US Imperialism

Caribbean Unity Tested As Election Interference Allegations Threaten Regional Trust