By Petra Noel-Arthur

The child appears without warning, arms outstretched. He moves with the certainty of recognition, pulling her into an embrace that bridges two worlds – his life just beginning, hers spent in the company of endings.

How many times has she held life in her hands at its final, soulful stage? Now, in this single gesture from a stranger-child, the circle closes.

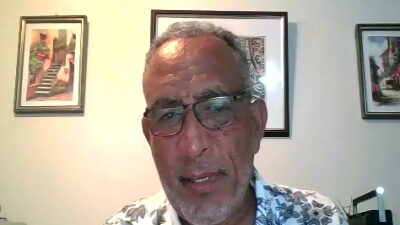

Priestess. Mother. Enigma. Maverick. Jewell Leacock wears these names like layers of ceremonial cloth, but the one that takes centrestage with channelled focus is this: owner, in-house mortician and managing funeral director of Leacock’s Funeral Services. For three years now, she has worked in Barbados as one of the few women in this male-dominated industry.

Registering the business in 2006, Jewell had no idea when or how it would start. And so, she waited; quietly nurturing the qualities and experiences that would be necessary to sustain her dreams. Today, she doesn’t see herself as a disruptor but rather as a woman reclaiming what was always hers – a deep desire to serve the dead and their families and to contribute, both professionally and creatively, to an ancient tradition once led by women.

Throughout antiquity, women were the primary caretakers of the dead. They washed bodies, anointed them, dressed them with salts and spices for preservation and immediate burial. Then came industrialisation.

The American Civil War demanded bodies be preserved for longer journeys home. Science replaced ritual. And women – deemed intellectually incapable of the embalming process – were slowly, then all at once, erased from funerary practice.

The irony burns: today, 72 per cent of mortuary science graduates are women. They dominate the classroom but vanish before reaching leadership positions. The glass ceiling in this industry is built from mahogany and lined with satin.

Jewell, 47, learned early how to survive erasure.

Born into the traditional framework of a nuclear family where love was constant but silent, she found her strength in solitude whenever life’s promise of hope springs eternal, was denied or fragile.

“Life was pretty normal until I got expelled from The Alexandra School,” she reflected, her voice steady as a held breath. “That’s when everything changed for me. I was not prepared for that. It was rough. I was very quiet and timid. I think that experience made me go further inwards and then anger.”

With the expulsion came regret, guilt and self-doubt but also the resilience forged in the depths of solitude and rebellion that contributed to her graduating from The Foundation School and completing a degree three years later, in mortuary science and funeral service from the McAllister Institute in Manhattan, New York. However, as often is the case in life, lessons in the form of events are repeated until they have been learned at a master level and the impact of the expulsion was a seed that had already taken root years before and now in full bloom.

This seed of doubt had been planted long before when her Class 4 primary school teacher predicted, offhand and cruelly, that nothing would come of Jewell. She would be pregnant by 16, he said. Her budding pubescent body, facial features, innocence and timid personality all became grounds for condemnation. What future could she look forward to when she herself was read as a failure by a teacher she trusted?

“I felt disconnected and ashamed,” she said. “I did not know what he was seeing that would make him draw that conclusion and that made me question everything I thought I knew at the time and I went into secondary school very unsure about who I was as a result.’’

And yet, despite the odds, Jewell became one of the youngest qualified morticians in Barbados at age 21, starting her career at Belmont Funeral Home.

This time, however, the struggles came from within. Though Jewell had stumbled along life’s path to stand victorious, her youthful (in) experience had not prepared her for the trials of death amidst so much life.

“I don’t want to say that my heart was not in it, but I did not understand what I was doing from a soul level,” she admitted. “Yes, I knew how to embalm and do all the stuff, but I was not connected to the role and I didn’t understand the ways of people as yet. Taking time away from the industry, I found that connection. Death is heavy, especially for death care professionals and I just wasn’t equipped as a young girl who had no guidance or trusting mentor to help me make sense of it all.”

For 18 years she retreated to the Barbados Forensic Lab where she immersed herself in the study

of various forensic sciences, specifically forensic pathology. There, she assisted in forensic autopsies and carried out morgue attendant duties, gaining firsthand experience in the intricate science of uncovering truth through death.

Detaching from the dream that she had once cherished, the nearly two-decade hiatus from funeral services was a respite from numbness, from the flicker of unrealised potential threatening to go dark. Only after coming to terms with her hunger for something more – more of her highest potential – did she return.

Lyndhurst Funeral Home became the cradle that reawakened her reverence for mortuary science, for life, for dignity. It also became a battleground; proving to be ‘’excruciatingly challenging’’ yet transformative for Jewell.

“Lyndhurst prepared me to stand on my own,” Leacock said. “It represented everything that the patriarchy stood for and that is the place that I came face to face with what forced me to stand up for myself. I loved the work I did and was able to do there, but I don’t love how I was treated.”

That experience propelled her to step out on her own in quiet and sturdy faith. Knowing that working for herself would offer more and, inspired by the footsteps of a few brave women before her, most notably the late “shero” Jo-Anne Jones, she chose to stand on her own.

Today, Jewell is carving out her place in Barbados’ funeral industry, not only as a mortician and business owner, but also as a visionary reimagining how the dead are honoured and celebrated; noting that the cookie-cutter mold of colonialised Western funerals does not always honour the life that was lived.

“My overall thing is to reflect the deceased while respecting the family’s finances,” she explained. “To make it a personal and heartfelt experience and not what ‘they’ say it has to be. We can have a funeral service in a garden setting like this one too. A little imagination and creativity can go a long way,’’ yet she acknowledges that dreamers and creators are often punished for daring to challenge the gatekeepers, but that has not been enough to stop her.

Leacock’s Funeral Services is symbolised by the ankh, the ancient Egyptian symbol bridging life and death. Jewell’s vision is clear: “You can be inspired by death to live a better life. The only thing we can do is enjoy the interval between birth and death while making ourselves better with mastery.”

And so, as this story began, it ends. Having completed the maze at Andromeda Gardens, the child walks up the sloping steps, passes the restaurant and its occupants, and enters the main house and declares: “I came back.”

He always does. They all do. In memory, in ritual, in the hands of women like Jewell who remember what the world forgot – that tending the dead is sacred work, and it was always theirs to do.